This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Intro to Radio Waves

Before we can start discussing Amateur Radio (or Ham Radio), we need to talk a little bit about radio waves. We'll explore this topic in much more detail later on, but for now, let's look at some foundational concepts.

Imagine the radio in your car could not only listen but also transmit on any frequency you like. What would happen as you move up and down the dial?1)

Starting in the FM radio range, let's turn the dial down:

- At 88.1 MHz, you'd be transmitting on top of CBC Radio 1 FM (in the Vancouver area).

- At 0.690 MHz (or 690 kHz) you'd be transmitting on top of CBC Radio 1 AM (in the Vancouver area).

- Around 1 kHz (or 1000 Hz) you'd be interfering with military submarine radio communications.

At this point, you should start thinking about the relationship between MHz, kHz, and Hz. We'll add more to the list below.

There's a lot of stuff in between, but it's pretty much radio waves all the way down. However, turning the dial above the FM radio stations yields some surprises:

- At 2.4 GHz (or 2400 MHz) and 5 GHz (or 5000 Mhz), you'd be interfering with WiFi signals.

- Between 30 and 120 THz (30,000 and 120,000 GHz), you'd be in the mid-infrared range and your antenna would start to feel warm.

- At 400 THz, the antenna would start glowing red.2) By increasing the frequency, you'd go through all the colours of the rainbow until the last purple would vanish around 790 THz.

- Between 790 THz and 30 PHz (30,000 THz) you'd create UV rays, which are invisible but could blind you.

- Between 30 PHz and 30 EHz (30,000 PHz) you'd create X-rays, which we could be used to take pictures of your bones.

- And passed that you'd create gamma rays.

Electromagnetic Spectrum

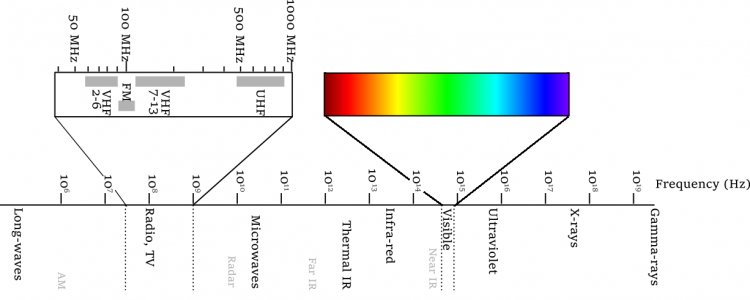

So radio waves are a small part of what we call the Elecromagnetic Spectrum3), which also contains visible light and a lot of other invisible stuff:

Take a moment to look at the spectrum and see which terms you're not familiar with.

Let's now unpack some of what we just saw...

Hz

A Hertz (Hz) is a measure of how fast something vibrates. For example, the A-string of a guitar vibrates 440 times per second, so we say that it vibrates at 440 Hz. The next A (an octave higher) vibrates twice as fast at 880 Hz. The human ear can hear sounds between roughly 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz.4) With sound, the higher the frequency, the higher the pitch. With light, the higher the frequency, the “colder” the colour.

Electromagnetic (EM) waves and sound waves are completely different things. The only thing they have in common is that “something” oscillates, but many things oscillate so that's not saying much. Just seeing “Hz” doesn't tell you anything about what it is that's oscillating in the same way that seeing “°C” doesn't tell you anything about what it is that has temperature. “Hz” is a unit of measure, not a thing itself.

Now back to radio waves...

Without going into too much detail (yet), radio waves are created by oscillating electric currents. How many times this current oscillates per second is called the frequency, which is measured in Hz (or kHz, MHz, GHz).

The “k” (kilo), “M” (mega), or “G” (giga) that you'll often see in front of Hz is a quick way of multiplying by 1000:

| 1 kHz | = 1000 Hz | = 103 Hz (1 followed by 3 zeros) | |

| 1 MHz | = 1000 kHz | = 1,000,000 Hz | = 106 Hz (1 followed by 6 zeros) |

| 1 GHz | = 1000 MHz | = 1,000,000,000 Hz | = 109 Hz (1 followed by 9 zeros) |

These prefixes are not only used for frequencies. You've seen them in other places before:

- 1 km (kilometer) = 1000 m (meter)

- 1 MW (megawatt) = 1,000,000 W (watt)

- 1 GB (gigabyte) = 1,000,000,000 B (byte)

So no matter what the unit of measure, these prefixes mean:

- kilo (k) = a thousand

- mega (M) = a million

- giga (G) = a billion

- tera (T) = a trillion

This might be a good time to mention that we also have prefixes for small units (more on this later):

- milli (m) = a thousandth

- micro (μ) = a millionth

- nano (n) = a billionth

- pico (p) = a trillionth

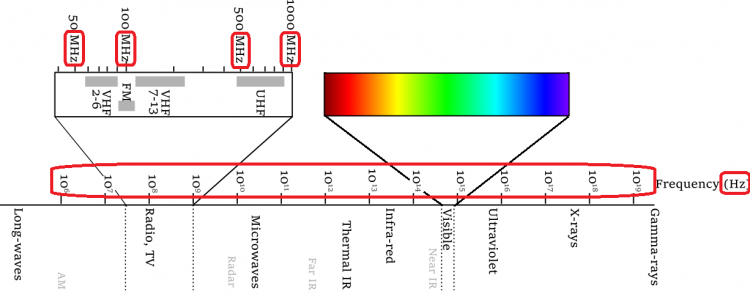

Now, let's take another look at the Electromagnetic Spectrum picture. You should be able to make sense of pretty much all of it:

- FM radio and TV broadcasting is between 50 MHz and 1000 MHz (called VHF and UHF bands).

- But some radio waves go even lower than 106 Hz (or 1 MHz).

- Above radio waves are Microwaves, Infrared, Visible light, UV, Xray, and Gamma-rays.

Next, let's look at where Ham radio frequencies are on that spectrum.

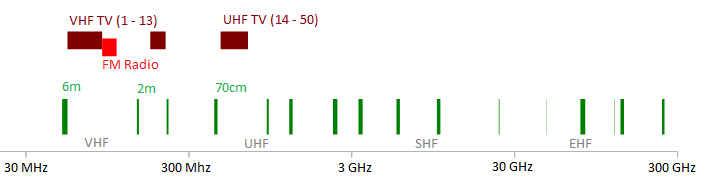

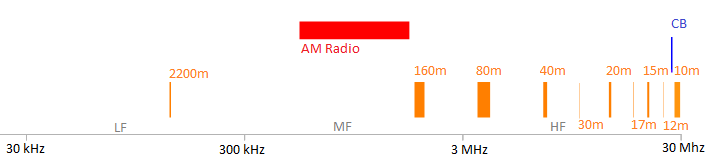

Ham Bands Overview

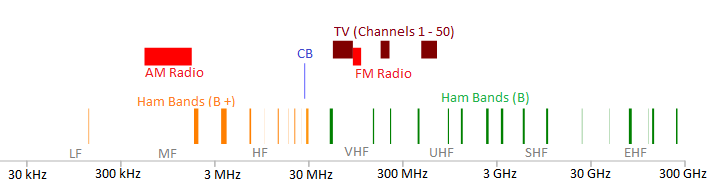

Ham radio operators are allowed to transmit on very specific slices of the Electromagnetic Spectrum depending on which qualifications we have (“Basic” or “Basic +”):

- In green are VHF, UHF, SHF, and EHF bands that require only the Basic qualification.

- In orange are LF, MF, and HF bands that require Basic with Honours, Basic with Morse, or Basic with Advanced qualification.

- In blue are CB bands, which don't require any qualification but can only be used with unmodified CB radios at relatively low power (for reference).

- In red are the AM and FM radio broadcasting bands (for reference).

- In maroon are the old VHF (1-13) and UHF (14-50) TV channels.5)

Bandwidth

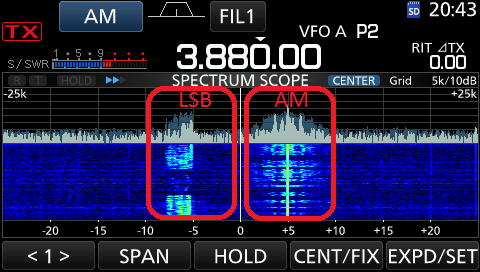

Although the human ear can detect sounds between 20 Hz and 20 kHz, human speech typically uses sounds between 300 Hz and 3000 Hz. Modulating these sounds (more on that later) onto a radio wave means that the radio will actually transmit over a range of frequencies that we call bandwidth. For example, using SSB, the bandwidth would be 2700 Hz (300 Hz to 3000 Hz). So a radio tuned to transmit at 3.800 MHz would actually transmit between 3.7973 MHz and 3.7997 Mhz. Using AM, the bandwidth would be 6 kHz so the transmitted frequencies would be between 3.797 MHz and 3.803 MHz.

We'll explore this in much more detail later, but for now, the important concept is that to transmit a signal, the radio must transmit over a range of frequencies, not just one single frequency. This range is called bandwidth.

In addition to only being allowed to transmit on specific frequencies, ham operators also have to make sure that they don't transmit over a greater bandwidth than allowed for the specific frequencies.

That is, there are restrictions on where we transmit on the spectrum as well as how wide the transmissions are.

This is important because different modes have different bandwidth requirements. From lowest to highest:

| Mode | Required Bandwidth |

|---|---|

| CW | ~300 Hz |

| 300 Baud Packet | ~600 Hz |

| SSB Voice | 2.7 kHz |

| Slow Scan TV | 3 kHz |

| AM Voice | 6 kHz |

| FM Voice | 20 kHz |

| Fast Scan TV | 6 MHz |

We'll look at that picture in more details soon, but for now, let's just point out how the AM signal is twice as wide as the SSB signal.

Certificate Qualifications Overview

There are three different qualifications: Basic, Morse, and Advanced.6)

- Basic requires 70% to pass, but 80% or greater gives Honours privileges.

- Morse requires 5 wpm.

- Advanced is a different test that require more electronics.

| Privilege | Basic | Basic with Honours or Basic + Morse 5wpm | Basic + Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequencies above 30 MHz | Y | Y | Y |

| Power up to 250 W | Y | Y | Y |

| Frequencies below 30 MHz | N | Y | Y |

| Power up to 1 kW | N | N | Y |

| Build or Modify Radios | N | N | Y |

| Manage a repeater | N | N | Y |

| Remote Control Radios | N | N | Y |

The Basic (70% ‒ 79%) certificate gives access to these frequencies:

VHF and UHF bands are local bands (more on that later). Your range could vary between 1km and 100km depending on your setup (more on that later).

The “2m band” (144 ‒ 148 MHz) is the most popular popular band above 30 MHz. You should make sure your first radio covers at least this band. Radios that can cover both the “2m” and the “70cm” bands are very common.

The Basic with Honours (80% or more) certificate adds access to these frequencies:

HF bands are “long range” bands. Depending on the conditions, you could talk to someone in the next town or halfway around the world.

Full Frequency List

Here is the full frequency list. Highlighted information might be on the test.

- The Band name is given in meter or cm. You'll need to know them.

- The Maximum Bandwidth is the maximum width of the radio signal. You'll also need to know these.

- Under License,

- “B” means Basic, and

- “B+” means Basic with Honours, or Basic with Morse, or Basic with Advanced.

- The Notes in the last column are really important since some bands have restrictions you need to be aware of.

| Band | Range (MHz) | Max Bandwidth | License | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | 2200m | 0.1357 ‒ 0.1378 | 100 Hz | B + | D, 1 |

| MF | 160m | 1.8 ‒ 2.0 | 6 kHz | B + | |

| HF | 80m | 3.5 ‒ 4.0 | 6 kHz | B + | |

| HF | 60m | 5.332, 5.348, 5.3585, 5.373, 5.405 | 2.8 kHz | B + | 2 |

| HF | 40m | 7.0 ‒ 7.3 | 6 kHz | B + | 3 |

| HF | 30m | 10.10 ‒ 10.15 | 1 kHz | B + | D, 4 |

| HF | 20m | 14.00 ‒ 14.35 | 6 kHz | B + | |

| HF | 17m | 18.068 ‒ 18.168 | 6 kHz | B + | |

| HF | 15m | 21.00 ‒ 21.45 | 6 kHz | B + | |

| HF | 12m | 24.89 ‒ 24.99 | 6 kHz | B + | |

| HF | 10m | 28.00 ‒ 29.7 | 20 kHz | B + | |

| VHF | 6m | 50 ‒ 54 | 30 kHz | B | |

| VHF | 2m | 144 ‒ 148 | 30 kHz ¥ | B | |

| VHF | 135cm | 219 ‒ 225 | 100 kHz | B | 5 |

| UHF | 70cm | 430 ‒ 450 | 12 MHz | B | ☆ |

| UHF | 35cm | 902 ‒ 928 § | 12 MHz | B | ☆ |

| Range (GHz) | |||||

| UHF | 1.24 ‒ 1.30 | B | ☆ | ||

| UHF | 2.30 ‒ 2.45 ‡ | B | ☆ | ||

| SHF | 3.3 ‒ 3.5 | B | ☆ | ||

| SHF | 5.650 ‒ 5.925 | B | ☆ | ||

| SHF | 10.0 ‒ 10.5 | B | ☆ | ||

| SHF | 24.00 ‒ 24.05 | B | |||

| SHF | 24.05 ‒ 24.25 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 47.0 ‒ 47.2 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 76.0 ‒ 77.5 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 77.5 ‒ 78.0 | B | |||

| EHF | 78.0 ‒ 81.0 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 81.0 ‒ 81.5 | B | 6 | ||

| EHF | 122.25 ‒ 123.00 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 134.0 ‒ 136.0 | B | |||

| EHF | 136.0 ‒ 141.0 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 241.0 ‒ 248.0 | B | ☆ | ||

| EHF | 248.0 ‒ 250.0 | B |

- ¥ Since Fast Scan TV requires 6 MHz of bandwidth, it can't be transmitted below the 70cm band.

- § The 902 ‒ 928 MHz band may be heavily occupied by licence exempt devices, which are lower power devices that don't require a license but can't be interered with (like cordless phones)

- ‡ The 2.30 ‒ 2.45 GHz band is shared with Industrial Scientific Medical (ISM) licence exempt devices.

Non-ham frequencies for comparison:

| Range (MHz) | Details | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF | 0.535 ‒ 1.705 | AM Radio | |||

| HF | 26.965 ‒ 27.405 | CB (40 channels) | |||

| VHF | 54 ‒ 88 | VHF TV Channels 2 ‒ 6 | |||

| VHF | 88 ‒ 108 | FM Radio | |||

| VHF | 174 ‒ 216 | VHF TV Channels 7 ‒ 13 | |||

| UHF | 462.550 ‒ 462.725 | FRS (channels 1 ‒ 7 and 15 ‒ 22) | |||

| UHF | 467.5625 ‒ 467.7125 | FRS (channels 8 ‒ 13) | |||

| UHF | 470 ‒ 692 | UHF TV Channels (14 ‒ 50)7) | |||

Name of frequency ranges:

| Name | Abbreviation | Frequency Range |

|---|---|---|

| Very Low Frequency | VLF | 3 ‒ 30 kHz |

| Low Frequency | LF | 30 ‒ 300 kHz |

| Medium Frequency | MF | 300 ‒ 3000 kHz |

| High Frequency | HF | 3 ‒ 30 MHz |

| Very High Frequency | VHF | 30 ‒ 300 MHz |

| Ultra High Frequency | UHF | 300 ‒ 3000 MHz |

| Super High Frequency | SHF | 3 ‒ 30 GHz |

| Extremely High Frequency | EHF | 30 ‒ 300 GHz |

Important Notes

Information quoted here was taken from ISED's RBR-4.

| D | For the 2200m and 30m bands, the maximum bandwidth allowed is too narrow for phone (voice) transmissions. Therefore, only digital or CW modes are allowed. |

|---|---|

| ☆ | Secondary User “means that transmissions shall not cause interference nor be protected from interference from stations licensed in other services operating in that band. Operating provisions defined below are excerpts from the Canadian Table of Frequency Allocations, which is amended from time to time.” Basically, this means that the Amateur Radio Service is secondary to some other service and that we must yield the frequency when they need it. We must not cause interference to these other services, and we must accept that they have first priority and may interfere with us at anytime. |

| 1 | “Stations in the amateur service using frequencies in the band 135.7 ‒ 137.8 kHz shall not exceed a maximum radiated power of 1 W (e.i.r.p.) and shall not cause harmful interference to stations of the radionavigation service.” This is the 2200m band referred to in Note D. It is mostly used for experimental purposes and transmissions must be at very low power and can't cause interference. |

| 2 | “Amateur service operators may transmit on the following five centre frequencies: 5332 kHz, 5348 kHz, 5358.5 kHz, 5373 kHz, and 5405 kHz. Amateur stations are allowed to operate with a maximum effective radiated power of 100 W PEP and are restricted to the following emission modes and designators: telephony (2K80J3E), data (2K80J2D), RTTY (60H0J2B) and CW (150HA1A). Transmissions may not occupy more than 2.8 kHz centred on these five frequencies. Such use is not in accordance with international frequency allocations. Canadian amateur operations shall not cause interference to fixed and mobile operations in Canada or in other countries and, if such interference occurs, the amateur service may be required to cease operations. The amateur service in Canada may not claim protection from interference by the fixed and mobile operations of other countries” This band is composed of 5 discrete channels and transmission is restricted to these exact frequencies. Other amateurs around the world do not have permission to transmit on these frequencies so Canadian amateurs are secondary users, which mean that they must stop transmitting if they interfere with other users. |

| 3 | “The use of the band 7.200 ‒ 7.300 MHz in Region 2 (North America) by the amateur service shall not impose constraints on the broadcasting service intended for use within Region 1 and Region 3 (Europe and Asia).” Although Amateurs are allowed to transmit between 7.200 ‒ 7.300 MHz in North America, they'll have to work around foreign broadcasting stations who also use this section of the spectrum. |

| 4 | “The use of the band 10.100 ‒ 10.150 MHz by the amateur service in Canada is not in accordance with the international frequency allocations. Canadian amateur operations shall not cause interference to fixed service operations of other administrations and if such interference should occur, the amateur service may be required to cease operations. The amateur service in Canada may not claim protection from interference by the fixed service operations of other administrations.” Other amateurs around the world do not have permission to transmit on these frequencies so Canadian amateurs are secondary users, which mean that they must stop transmitting if they interfere with other users. |

| 5 | “In the band 219 ‒ 220 MHz, the amateur service is permitted on a secondary basis. In the band 220 -‑ 222 MHz, the amateur service may be permitted in exceptional circumstances on a secondary basis to assist in disaster relief efforts.” |

| 6 | “The 81.0 ‒ 81.5 GHz band is also allocated to the amateur and amateur-satellite services on a secondary basis.” |

Questions

- B-001-003-001

- B-001-004-002

- B-001-004-004 → B-001-004-006

- B-001-005-002

- B-001-006-005 → B-001-006-006

- B-001-008-004 → B-001-008-006

- B-001-010-003 → B-001-010-004

- B-001-010-007 → B-001-010-008

- B-001-010-010 → B-001-010-011

- B-001-015-001 → B-001-016-011

- B-001-018-004

- B-001-020-004